Yoginī & Mātṝkās: Ecstatic Divine Celebration

Introduction

Across cultures and continents dance and music has always been part of the human celebration and also a way to transcend the profane to achieve divine joy, bliss. In some parts of the world dance remains imbedded in sacred rituals. I have participated in such ceremonials in the area of the Golf of Guinée. Drums and dance are methods of invocation, and ways to celebrate the encounter with the divine. In Cuba the Santeria kept some of those elements. In India, the pujas to Kali or other divinities are a vivid testimony of celebrating the encounter with the divine through sound and dance .

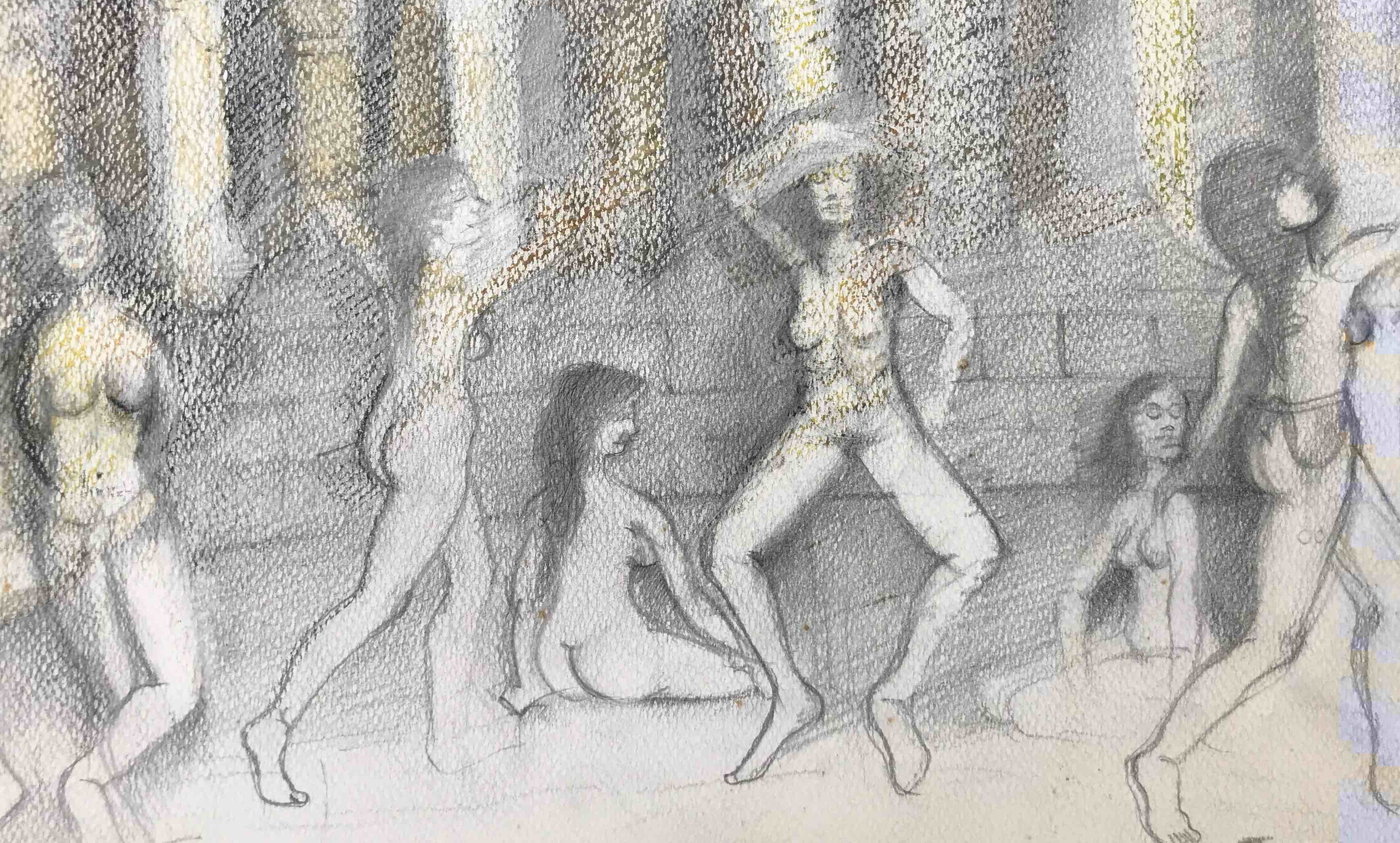

In this paper I would like to analyse different sources of information that we have regarding the Divine Dancing Celebration. (I am not speaking about the Indian classical dance roots, even though they may have many commonalities as probably both in some contexts were seen as a religious path .) My intention is to bring forth the dynamics of the sculptural expression of rapturous dance that convey transformation and bliss like the one performed by Śiva Naṭarāja combine with the heroic and also ecstatic dances that maybe give immortality as describe in the Rig Veda when Indra is the dancer …”the immortal dances forth his hero exploits”. During centuries in India, in sacred or profane literature as well as in visual arts, the stories have a recurrent theme that revolves around dramatic fights between heroes or heroines against obstacles depicted as demons. After a general introduction to the studies of the mātṝkās, I would like to focus on the dance imagery of groups of goddesses that were depicted during the period when all the spiritual streams were influenced by the Tantras.

Matrikas (mātṝkās) and other Groups of Female Divinities

The Power of Many

I have travelled extensively in India and visited Asian collections in museums, to admire the amazing diversity of representations of the Divine in sculptures and trying to understand the legends around them. In his remarkable study published in 1986 professor Michael Meister said ‘written evidence rarely fits available images’ . Fortunately in the last fifteen years, Indologists have given great attention to the mātṝkās and yoginīs resulting in new observations and studies of ancient texts and inscriptions: Scattered Goddesses written by professor Padma Kaimal; different compilations of academic essays from scholars by professor István Keul; the most revealing researches done by professor Shaman Hatley and a very enlightening paper The Company of Men- Early Inscriptional Evidence for the Male Companions of Mother Goddesses by professor Daniel Balog , and many others.

These studies helped me as a non-scholar (but a curious person) to acknowledge the diversity and common patrons that I have seen in sculptures, probably influenced by modes in a specific time, regional tendencies or schools of thoughts. Before I came in contact with the “yoginī world” I thought that the religious sculptures in India followed strict rules in how to depict a divinity or a heroic episode. I now have a better understanding of the expression of different religious streams: the traditional ones that want to honour the divine embodied in the stone according to distinctive canons; and the freer ones that grew parallel (mostly under the broad umbrella of the Tantras). I believe these last expressions, were more focused in complementing esoteric teachings or in giving a spiritual experience.

In ancient literature we find groups of divinities or semi divine entities (female or male) who were transmitting the idea of togetherness in their multiplicity and without showing a distinctive individuality: kinnaras, kinnarīs, yaksas, yaksīs, gandharvas, gandharvīs, apasaras, etc. The dakinīs mainly in tantric texts and imagery (mostly Buddhists) have more personal attributes and similarities with the yoginīs and mātṝkās. These divinities were not only defined by their attributes (personalities) but also by the power of the number of members of their groups. Multiplicity in oneness.

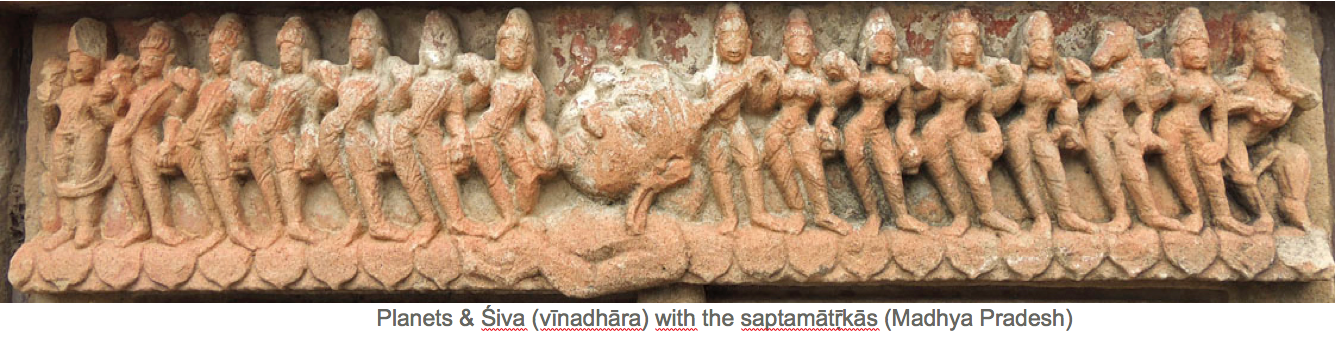

Early sets of divinities were created in Vedic times: gods with personalised attributes that became the guardians of the directions (dikpālas) varying in number of ten (including zenith and nadir), nine (including a centre point) or the most known eight cardinal points. The nine planets also were depicted in a group and around the 10th century, they appeared often in the same lintel as the mātṝkās or in a table close to them.

There are many theories and stories about how the mātṝkās came into the Indian pantheon and why they became known as ‘the mothers” mātṝkās, venerated across India and across the different religious streams and social backgrounds.

Some stories associate Skanda with the mātṝkās and these with Pleaides (Kṛttikā or Kārtikā ). Therefore one of Kanda’s names is Kārttikeya . He is also the ‘accidental son’ of Śiva or Agni who’s semen went in to the water and impregnated some prude sages’ wives who were swimming there. Those six women became ashamed of their pregnancy and when they delivered their sons, each one gave her new born to the fire which melted the bodies in one. Suddenly the women realized their maternal instinct and became loving mothers of the god. Skanda’s stories are associated with female entities that first were cruel and selfish and then became maternal. This ambivalence has accompany the early narratives of the groups of ‘dangerous’ mātṝkās.

Other groups are also seen as a prototype of the depiction of the mātṝkās in the company of a male gods: Kubera, god of wealth is accompanied by Lakṣmī goddess that brings prosperity and Hāritī already seen as protector of progeny. (In early stories Hāritī use to hunt children in order to feed her own hundred children. People began to pray asking her not to take away their progeniture. With time, she became the protector of children.) From the 2nd century until the 11th we find goddesses in the company of Kubera.

Some mothers of the directions related to the Vedic gods dikpālas were found in Orissan wall temples built around the thirteen century .

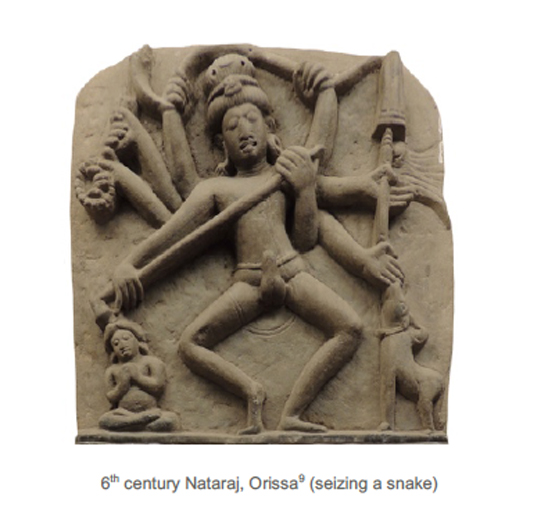

“Śiva infiltration into the group of Mothers is less than straightforward. Iconographic manuals generally prescribe that Vīrabhadra (“the gracious hero”) or Vīreśa (the lord of heroes) should accompany the seven mothers” say Balogh. How this Vīrabhadra became Vīṇādhara (the bearer of the instrument vīṇā) and both somehow became Śiva? What I understand from the scholarly studies is that Skanda (Karttikeya), the warrior hero became Vīrabhadra. Then, this gracious hero suffer an easy symbiosis with Śiva, the already powerful hero, the seizer of snakes (bhujagendrahāram), the killer of the elephant demon (gajāsura) and the Naṭarāja (the lord of the dance).

It seems too that Gaṇeśa did not replace Skanda but Kubera .

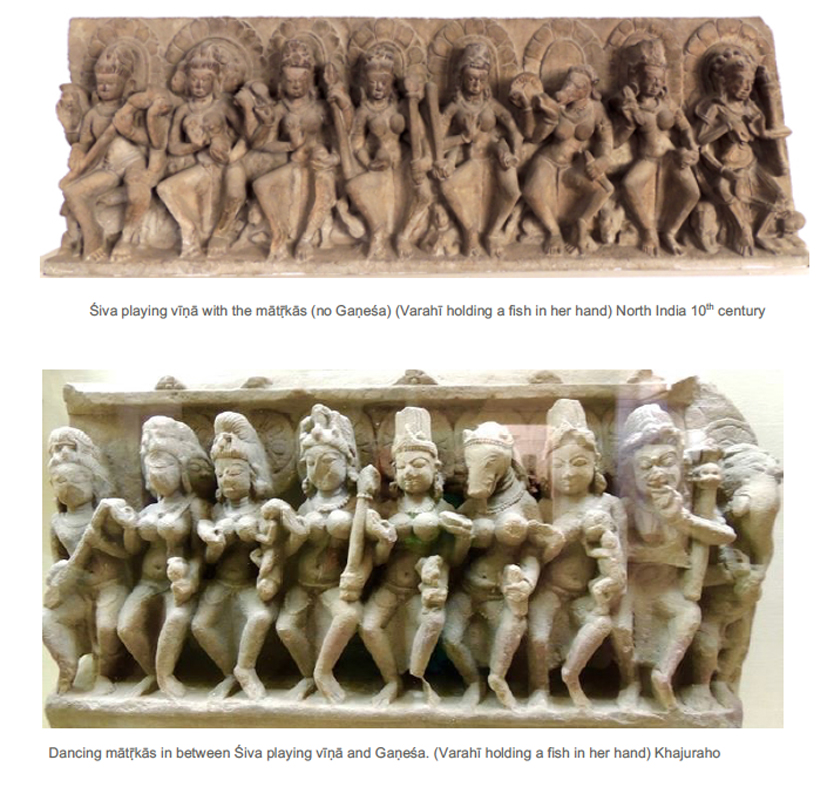

The most common depiction of several goddesses are in panels where seven mātṝkās (saptamātṝkās) have their own traditional vehicles. Sometimes all but Cāmuṇḍā are carrying children. They are between Śiva playing the vīṇā and Gaṇeśa. All have a halo (implying that they are divine). All the figures are dancing (suggesting some kind of ritual celebration).

Evolution and changes took place. The ‘wild mātṝkās’ became ‘domesticated’ and related to some Brahmanical gods. Brāhmanī is depicted with three heads as Brāhma; Maheśvari is holding a trident and accompanied by Nandi (Śiva’s bull); Kaumārī has a peacock as Kumāra (Skanda); Vaiṣṇavī is holding a conch and is accompanied by the eagle Garuda as Viṣṇu; Varāhī has a boar face as Varāha and often displays a more tantric look, accompanied by a buffalo and holding a skull and a fish in her hands; Indranī as Indra is riding an elephant; and Cāmuṇḍā, who is the strong but skeleton one, has no relation to any male god. She is also an interesting component to the iconography of the mātṝkās. She kept the awe inspiring look as a reminder of the ancient inscriptions that called the mothers terrifying creatures . In literature, mostly in Tantras, the mātṝkās are described as eight aśtāmātṝkās and Nārasiṃhī is often added(different names and identities were given to this eighth mother).

During centuries panels of mātṝkās were installed in many traditional temples. It seems also that the mātṝkās were venerated in their own temples. In Orissa I have seen many large sized mātṝkās. This attests their popularity as special places were consecrated to them. Śiva Vīṇādhara seems to have belong to these groups giving the idea that the Orissan mātṝkās were associated with music as it was the case all around India.

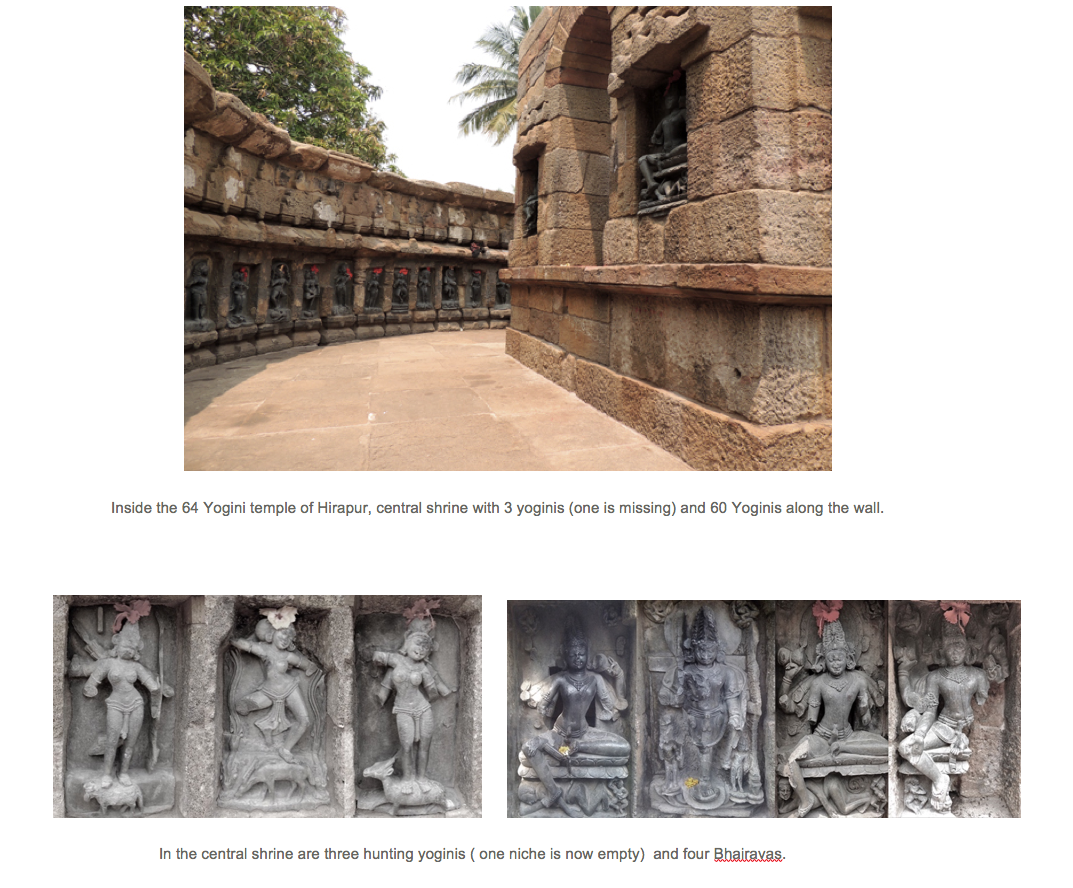

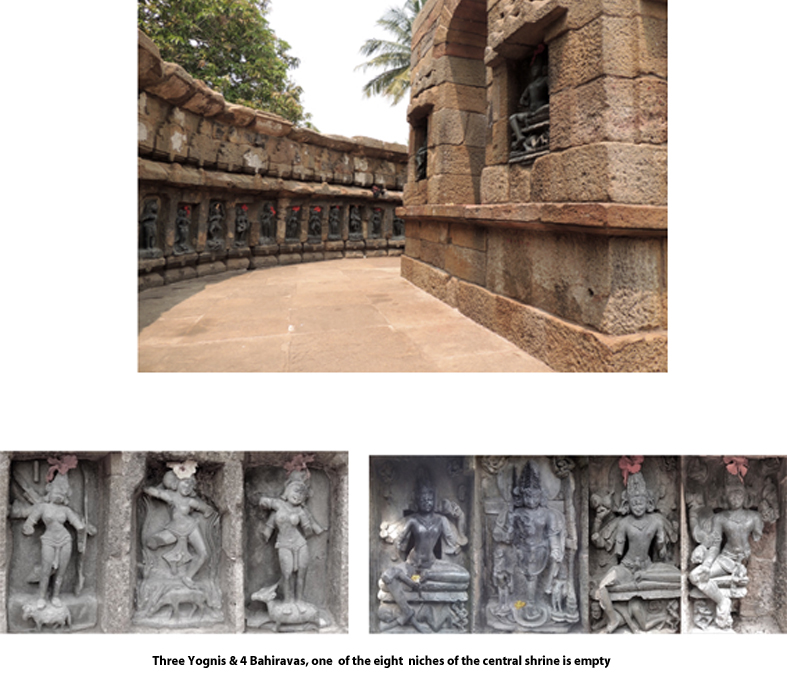

The plurality of goddesses seems to have gained the heart of spiritual streams and imaginative narratives. In several Tantras we find that the eight mātṝkās multiplying by eight qualities or mantras and became groups of sixty four yoginīs. Other stories tells that they emanated from the Devī to assist her in the combat against demons. Local insights expressed their devotion in temples of sixty four, sixty five , thirty two and eighty one . Some temples seemed to have the mātṝkās among their family of yoginīs. But no recognisable mātṝkās are found in the groups of yoginīs at the Hirapur and Ranipur Jharial temples in Orissa. In all the others groups of sculptures found around India it seems that the mātṝkās were part of the yoginīs’ family.

A set of dancing mātṝkās and Gaṇeśa are now in the very large yoginī temple of Bheraghat in Madhya Pradesh. They may have belong to an early mātṝkās temple as the sculptures of the sitting yoginīs are more elaborated according to the style in fashion on the 11th century. Also among the group of yoginīs are the conventional mātṝkās carved in the same style as the yoginīs as well as another Gaṇeśa with the same style of neckless (very damaged sculpture and half restored), another is also a male that could be Śiva vīṇādhara, and a third male, with the same style maybe is Bhairava (it is also a very damaged sculpture).

The yoginīs in their hypaethral temples are a wonderful display of plurality. The temples are a vibrant expression of liveliness, they are like a human body containing all the required energies to overcome any problem and allow the enjoyment of life to its full potential. Aesthetically the sculptures expressing their own personal powers create a harmonious set as the have the same carving style, similar size and type of decorations. Only the yoginī representing Mahiśāsumadinī is always standing while killing the buffalo demon, but if the set of yoginīs is sitting, all the goddesses are sitting, if they are standing, all of them are standing. There are not the same yoginīs in all the temples. Their narratives variate as if they were born to fulfil the necessities of a place and a specific mythological time. In addition to the Bheraghat temple two more temples with yoginīs in situ also survived the aging process and changing ideologies. In Orissa there are two beautiful yoginī temples: Hirapur & Ranipur Jharial. The four others are now empty temples (Khajuraho , Bharatsaderi , Dudhai and Mitauli ). Two other ‘cross road’ temples have several empty niches that could indicate that once they belonged to the yoginīs’ spiritual streams. They are located near Khajuraho. (Baratsaderi & Vyas Bhadora ). With time maybe other ruins and sculptures will be studied in depth and reconsidered as related with the yoginīs. This will indicating a more comprehensive presence of the yoginīs in India or even in the other countries that were influenced by Indian spiritual streams.

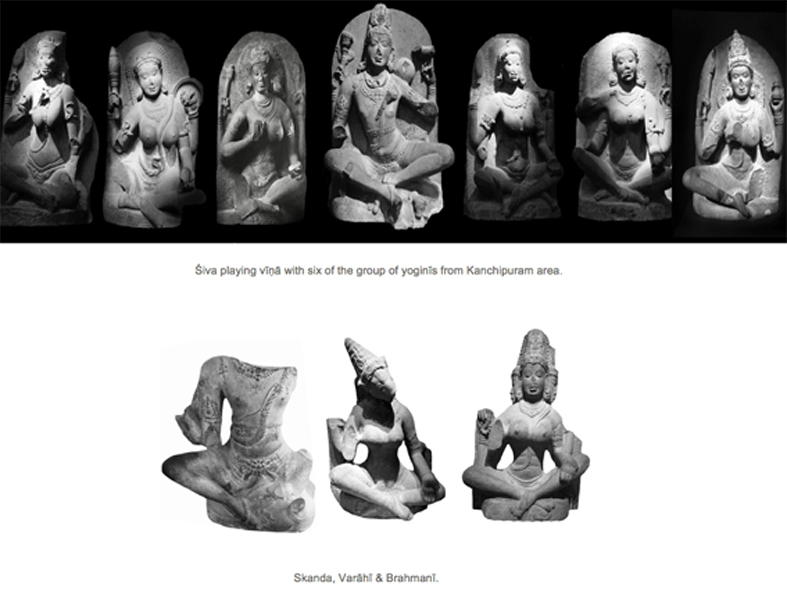

In Tamil Nadu, in the region of Kanchipuram a large group of sculptures were found suggesting that a yoginī temple was also in this area. The yoginīs sculptures were shifted from India to Paris where they were purchased by different museums in Europe and North America. Only one beheaded yoginī reminded in India and is displayed at the Chennai State Museum. Dr. Padma Kaimal did an amazing study of these ‘international’ yoginīs. In this group of Kanchipuram are two types of sculptures. The yoginīs and a Śiva are carved with a stone slab supporting their back. Two mātṝkās as well as the Skanda that is at the Chennai State Museum are slightly different, even though the style and decoration of the deities is similar. All these sculptures (yoginīs, mātṝkās, Śiva and Skanda) were found in the same spot in the area of Kanchipuram . The head of the mātṝkās and the Skanda are free standing without a back protection. Probably they were displayed in a central place, not against a wall. The Yoginīs and the Śiva probably were located in niches along the main wall. The temple may have had the display like the temple of Mitauli. In front the yoginī niches is a central shrine where the mātṝkās could have been, facing the yoginīs. Skanda may have had an honorific place in the middle of the central shrine.

The iconography and groups of mātṝkās evolved and their male companion changed too but legends and texts probably continued to relate the mātṝkās or yoginīs to Skanda.

In the tantric text of The Kaulajñānanirṇaya , Skanda-born of the union of the male and female principles- first appears as a young man acting foolishly. In his frenetic desire to preserve the knowledge he threw the book of knowledge into the sea. Bhairava became a fisherman (a low cast) and rescued the book that was swallowed by a fish. Skanda turned out to be Vaṭuka -Bhairava, surrounded by the yoginīs. He becomes the custodian of the yoginī knowledge.

Most of the tantric agamas are dialogs between Bhairava and the Devī. Bhairava being the formidable form of Śiva is considered to be the protector of the yoginīs.

At the yoginī temple in Hirapur there are four Bhairavas in the walls of the central shrine. Most of the yoginīs in Hirapur are standing. The few in dancing posture are those who celebrate a hunt or killing of a demon.

The ancient sculptural expression of the yoginī devotion and knowledge seem to have had many variations. Since early 20th century the interpretations of scholars and gurus display a wonderful diversity. From sex centred practices passing through bloody offerings to academic ones, all based on interpretation of texts, traditions, legends and imagery. This wide range of understandings open the door to even more hypothesis as more translations of related texts have been made and scholars travel to the sites.

In most legends around the world, the basic plots are around the tensions between good and bad where the good is supposed to win. The goal of Tantra is to transcend this duality and arrive to the state of unicity. To achieve this, different spiritual streams created their own path in order to stimulate the flow of energies in the body, to overcome obstacles and reach the highest state of consciousness. These tantric teachings were extremely powerful and only taught to those who were initiated. The rare powers, the siddhis techniques, were given after a certain time. The tantric texts were not supposed to become a self-instructing manual. It was required the guidance of a knowledgeable and enlighten master. The yoginī streams were diluted by time and events. Any ‘unique path’ that may be proposed ten centuries later would be mere speculation as there were no single spiritual streams. As we see in the diversity of the temples and yogini sculptures, evolving ideas and trends were adapted to express a mythical time. In that sense, a new revival is happening now. New spiritual streams and interpretations are rising from the almost extinguished fire.

We have a lot to learn from observation. The sculptures are ready to talk.

During the many centuries the Tantra shown all over the Indian subcontinent and many different tantric schools coexisted. Practices and ideology probably differed even in the same tradition according to the insight of the guru. Those religious streams were supported by royalties or powerful feudal lords who built the different temples to honour or seek protection of deities, mātṝkās or yoginīs.

The yoginī pantheon has great variety. Some are animal-headed, playing with concepts not too far from those found in shamanism. There are other yoginīs looking benevolent, favouriting an easy connection. Others have a threatening character as givers of their own strength to overcome negativity. Many yoginīs are wild looking. Often all types of yoginīs have weapons in their hand, a trident or skulls, while others are giving blessings.

Why was it said that there are four Bhairavas at the Hirapur temple and not four Śivas? Bhairava, is the fierce manifestation of the already wild and mighty Śiva. Bhairava shares his overpowering looks with the yoginīs: sometime he has wild hair, a strong expression in his eyes, and a mouth half open allowing his long fangs to be seen. Bhairava and yoginīs may have serpent collars or skulls collars. In their hands they hold skulls, tridents and other weapons, snakes, drums, rosaries, etc.

Bhairava represents the Supreme Reality. He is the power that can be only found in the present moment, the total integration of body (microcosm) and universe (macrocosm). He shows his total alertness having the phallus eructus, ready to vibrate with the divine feminine energy in the oneness of the Universe. In some representations he has a moustache and his vehicle is a dog. He is an extremely popular folk god and in villages takes the form of an orange painted stone with eyes and moustache. His shrines are close to the Devīs’ holy places. He appears as the protector of divine female energy. In rural India he is often called Bhero.

In the yoginī temple at Ranipur Jharial in Orissa the male god accompanying the set of dancing yoginīs is not Bhairava but Śiva Gajāsurasamhara. He is celebrating with the dancing yoginīs the mythical time of the destruction of the demon.

Professor Anamika Roy in her book about the yoginīs states: “The Yoginis dance because a deep-rooted tribal connection and a native trend can easily be detected in all the Yogini images ”. I totally agree that the local trends of ideas and artistic expression influenced the sculptures and for sure the sādhana . It is extremely probable that the yoginī followers at Ranipur Jharial used to dance in their spiritual practices to stimulate the flow of energy in the temple and the sacred vibration in their bodies. As Roy says later on in the same chapter: “The Yoginis stand at the juxtaposition of the cult and popular believes. ” She concludes the chapter saying: … “this was a dance of divine ecstasy, representing hermeneutical world of complex interpretations.” The dance of the yoginīs could have been influenced by tribal ecstatic dances but also by esoteric concepts and practices perceived as the sacred tremors, the sacred movements, (spanda), the primordial vibration of the Universe and of our being. Maybe refine perception and the earthy local-tribal practices came together in the temple of Ranipur Jharial. The famous tantric scholar Mark Dyczkowski says: …”the dynamic (spanda) character of absolute consciousness is its freedom to assume any form at will through the active diversification of awareness (vimarsa) in time and space, when it is directed at, and assumes the form of, the object of awareness.”

In the legends demons are bad but not totally bad. They gain merits during their life by praying to a god who has given them some powers and they become difficult to kill. Often, they have asked for boons like to be remembered. When the gods or goddesses finally kill the demon, they honor them by incorporating in their new names the name of the demon. Cāmuṇḍā got her name after killing the demons Caṇḍā (glowing with passion) and Muṇḍā (mean); Hinglaja after killing Hingol; Śiva became Gajāsurasamhara, etc.; and when Durga killed the great demon Mahiśa Asura (demon buffalo) she took the name of Mahiśāsuramardinī, the destroyer of the demon buffalo. I relate the multifaceted appearance of the demon to the chaotic, changing and multiplying thoughts that pollute the mind when we are stressed. To gain an unpolluted mind, to destroy the chaos of the mind, strong weapons are required like the trident, the symbol of ‘will power, action and knowledge’.

One of the many stories about Śiva killing the demon Gajāsura relates how Śiva wanted to teach a lesson to some arrogant sages who thought they knew everything and therefore they were beyond all the temptations of the world. Śiva visited the forest where they sages were preforming their rites, appearing as a young naked mendicant accompanied with the enchantress Mohinī as his wife. The sages became bewildered by the beauty of Mohinī and lost their minds. Meanwhile their wives fell for the young and naked Śiva. When the sages realized what had happened, they performed a black magic charm, which produced the elephant-demon Gajāsura who, overtaken by his inherited arrogance thought he had more strength than any other creature in the three worlds. Śiva went inwards in meditation to find the unlimited source of knowledge that gives all the rare powers (the siddhis). Imbedded by his own power, Śiva easily killed the demon and vibrating within his endless energy, danced in total bliss, vigorously, flagging the elephant hide of Gajāsura.

Daniel Balogh translate an inscription from around the 5th century, located at Badoh Pathāharī in Madhya Pradesh and he comments: “the text opens with a laudatory stanza dedicated to Rudra (Śiva), who is described as draped in bloody elephant skin (prāvṛtya … sa-rudhiraṃ gaja-carmma) and wearing a snake for a waistband (mahoraga-koṣṭha-sūtraḥ). The band of Mothers is also mentioned in this stanza; the context is much damaged but appears to be that Rudra dances in the funeral grounds accompanied by the band of benevolent Mothers (śiva-mātṛ-gaṇa).”

As I understand, demons and gods are not entities outside our minds and bodies. The battles are held inside us. The yoginīs are our own energies that in certain times we need to stimulate in order to find the strength to alleviate, deal or destroy the negativities (stress).

It is difficult to know which practices were perform in the yoginī temples but one of them probably was celebration. The bells and drums that still we can hear in the pujas to Kalī are powerful sounds to harmonise the energies in the body.

In The Kaulajñānanirṇaya, in the chapter XI we read:

“The Yoginīs grant the siddhis to the followers with the oblation mixed with the five nectars . Then, one becomes equal to the Yoginis. Identified with them, one is a knower of the Kaula and attains the siddhis being free from all obstacles and impediments. There is no doubt about it.’ (8-10)

“In the Kaula tradition, the five

“O Devī, one should carefully offer daily and also during special (naimittika ) rites, beef (gomāmsa ), ghee prepared from cow’s milk, blood, cow’s milk and curd. (12)

During these special rites performed with the keen desire for achieving the siddhis- the offering should be made without any fear and without any substitution, according to the dictates of the Kaula Agama. (13)”

In the chapters of The Kaulajñānanirṇaya different sorts of techniques are mentioned to achieve the state of Non-duality: meditations, prānāyāmas, mudrās, visualizations, yoganidrās, siddhis, etc., in order to harmonize the flow and integration of the energy of body-mind and Universe.

To begin with the process of reaching the non-dualistic state, The Kaulajñānanirṇaya states that one should abandon thinking in the dualistic way and should identify oneself with the non-dualistic path. To promote this change, to shake away the analytic process, the text discusses techniques that will destabilize the mind. These aim to free the mind from the bondage of established principles. Similar tools are found in almost all tantric texts. With outlandish or even contradictory statements, the teacher opens the path and destroy the restrictions of ancient paradigms. When the mind becomes liberated from the process of judging and analysing, the sādhaka can reach higher states of consciousness in ‘ecstatic divine celebration’. In the same XI chapter we find a description of the experience while dwelling in the state of all possibilities that the sādhaka attains through meditation. And it ends stating: “Now has been revealed the knowledge (jñānanirṇaya) of the oblation of the non-duality (43).” ”

For those who are interested in achieving the state of Non-duality, the iconography of mātṝkās and yoginīs may give light to their path through the delicate language of images and myths that transcend time frames and preconceived ideas.

Bibliography

Balog, Daniel, Academia.edu The Company of Men — Early Inscriptional Evidence for the Male Companions of Mother Goddesses, 2018.

Brighenti, Francesco, Śakti Cult in Orissa, 2001

Chitgopekar, Nilima Invoking Goddesses, Gender Politics in India Religion, 2002.

Dyczkowski, Marc S.G. The Doctrine of Vibration, 1987.

Hatley, Shaman, Academia.edu

“Converting the Ḍākinī: Goddess Cults and Tantras of the Yoginīs between Buddhism and Śaivism” Tantric Traditions in Transmission and Translation, edited by David Gray and Ryan Richard Overbey (Oxford University Press, Oxford University Press), 2016.

“Goddesses in Text and Stone: Temples of the Yoginīs in Light of Tantric and Purāṇic Literature.” In Material Culture and Asian Religions: Text, Image, Object, edited by Benjamin Fleming and Richard Mann. Routledge, 2014.

“Goddesses in Text and Stone: Temples of the Yoginīs in Light of Tantric and Purāṇic Literature.” In Material Culture and Asian Religions: Text, Image, Object, edited by Benjamin Fleming and Richard Mann. Routledge, 2014.

From Mātṛ to Yoginī: Continuity and Transformation in the South Asian Cults of the Mother Goddesses Transformations and Transfer of Tantra in Asia and Beyond, ed. by István Keul (Walter de Gruyter), 2012.

THE BRAHMAYALATANTRA AND EARLY SAIVA CULT OF YOGINIS,

UMI Dissertation Services, 2007.

Kaimal, Padma Scattered Goddesses, Travels with the Yoginis, 2012.

Keul, István (Ed.) Transformations and Transfer of Tantra in Asia and Beyond, 2011

‘Yoginī’ in South Asia, 2013.

Meister, Michael W JSTOR.org, Regional Variations in Mātṝkās Conventions, Artibus Asiae Publishers, Vol 47,No. 3-4, 1986.

Mukhopadhyaya, Saktari; Dupuis, Stella, The Kaulajñānanirṇaya, 2012.

Panikkar, Shivaji K. Sapta Mātṝkās, Worship and Sculptures,1997.

Rangarajan, Haripriya Images of Vārāhī, An iconographic study, 2004.

Roy, Anamika, Sixty-Four Yoginis, Cult, Icons and Goddesses, 2015.